“I’ve stood in towering old-growth forests, listening to the rain filtering down through the canopy while ravens and wrens sing,” the Canadian artist Julya Hajnoczky tells me. “I’ve also walked through forest fire sites, surrounded by still-standing charcoal-black tree trunks on a forest floor carpeted in lush green regrowth, hearing Swainson’s thrushes’ flute-like calls spiraling up into the sky. I’ve been in both fog and wildfire smoke so thick it was hard to breathe.”

For five years and counting, Hajnoczky has worked out of the Mobile Natural History Collection Laboratory. Nicknamed “the Alfresco Science Machine,” this lab-on-wheels is a repurposed utility trailer, converted by the artist into a camper and workspace. During that time, she’s traveled throughout Western Canada (and beyond), spending eight to ten weeks a year on the road, between spring and fall, exploring wild ecosystems.

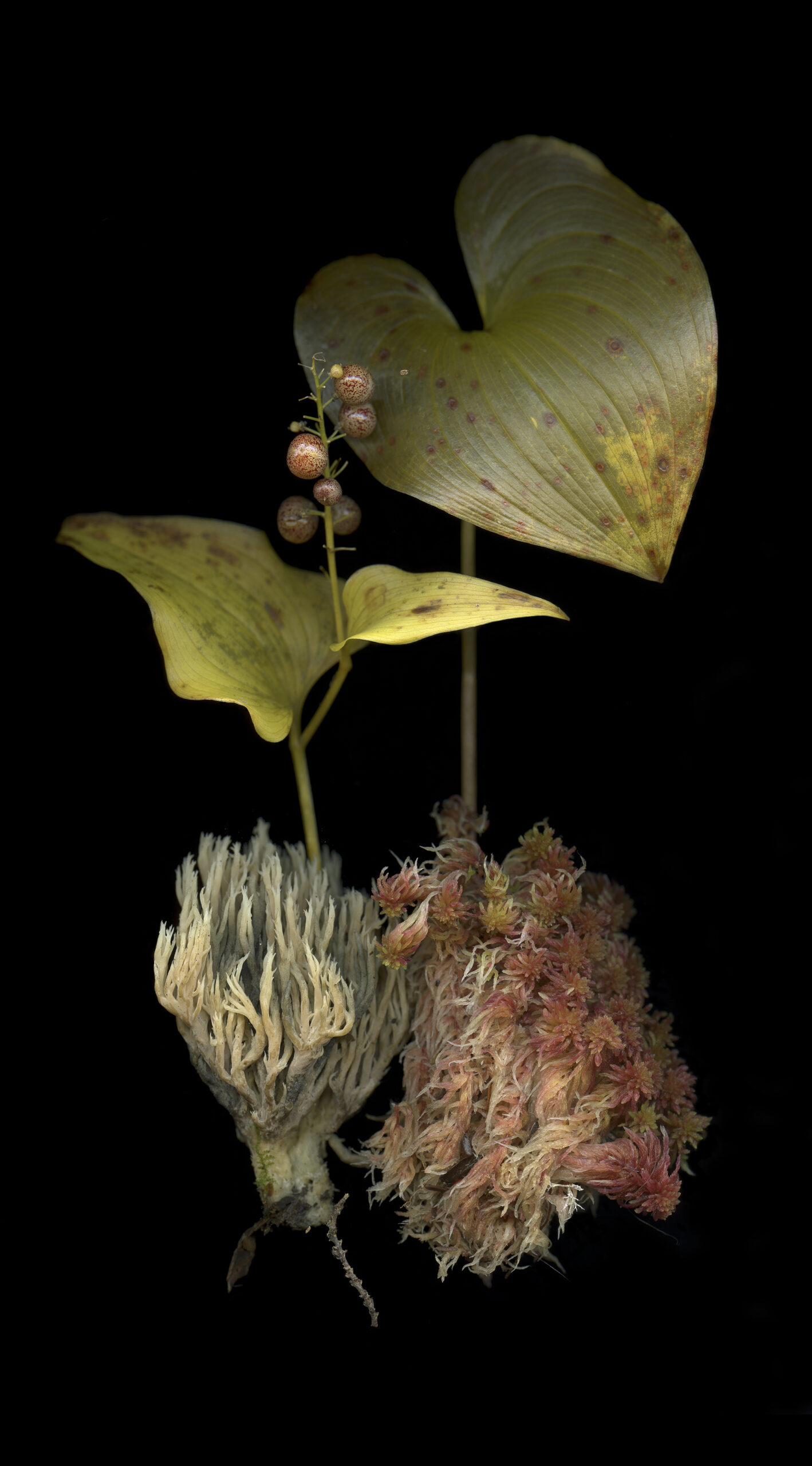

After extensive research in each of these ecosystems, she collects specimens—samples of fungi, moss, grasses, shells, deceased insects, and more—and creates miniature landscapes. The final compositions aren’t “photographed” in the traditional sense, using a camera. Instead, the artist uses a high-resolution scanner.

Hajnoczky’s use of the scanner means that she captures an astonishing level of detail, transforming the tiniest scenes into vast and elaborate vistas. Her work is an ode to the natural world during a time of catastrophic change, transforming living specimens and preserving them in a new kind of cabinet of curiosities. Today, the birds are singing, but tomorrow, they might be choked by smoke. That knowledge permeates the photographs, infusing them with a sense of loss as well as wonder.

But perhaps more than loss, Hajnoczky’s work inspires the almost physical ache of longing—to touch the dirt, smell the flowers, and hear the ravens. Throughout her travels, the artist has inhaled the scent of sagebrush wafting over dry grasslands. She’s listened to grasshoppers jumping across a flaxseed prairie, the sound of seedpods echoing like rattles. She’s tasted salt in the air while exploring for mussels and chiton shells along the beach. Looking at her photographs, we can almost taste it too.

We asked Hajnoczky more about the Mobile Natural History Collection Laboratory and her life on the road.

How have you chosen the ecosystems you’ve documented thus far? What do you look for in the places you visit?

“There are a lot of factors that go into selecting the places I do my fieldwork. My art practice revolves around my fascination and wonder at the incredible complexity of ecosystems, so the reading and research that I do often lead me to discover intriguing stories about how a certain set of living organisms are connected in a given ecosystem. I then decide to go study these ecosystems in person.

“Now that I’ve been working on this particular body of work for about five years, there are some places I like to return to over and over, in different seasons, to get to know them much more intimately. Sometimes, that’s because the biodiversity is so rich; sometimes, it’s because it’s an ecosystem at risk and I feel a sense of urgency to document the things still living there.

“I’m also looking for ecosystems I haven’t been to at all yet. The arctic regions of Canada, for instance, are high on my current wish list. This spring I was able to do a residency at Point Pelee National Park in Eastern Canada where I could do an in-depth exploration of a marsh habitat for the first time.

“From a practical standpoint, I often look for places where I can get permission to gather specimens; for instance, I obtain Collections Permits from Parks Canada to work in various national parks, or I work on private property as part of an artist residency like the Empire of Dirt. I like to be able to stay right on site to do my work, which usually means looking for parks with campgrounds, preferably with power so I can run my equipment, although I can make do with portable power banks if need be.”

Can you tell me a bit about your life on the road? What does a day in the lab look like for you?

“The lab is a combination workspace and living space, but it’s really quite small. I tell people I’m either in bed, or I’m outdoors! A day in the field always starts with a good coffee, listening to what birds are out and about in the neighborhood. If it’s my first day somewhere, I usually spend a good couple of hours just wandering my campsite, seeing what is growing there.

“On subsequent days, I’ll pick a trail in the area and explore that. I stop every couple of feet along the trail and spend an inordinate of time taking snapshots of the things I’m seeing, recording them that way or using iNaturalist’s Seek app on my phone to identify and keep track of everything around me. Sometimes I’ll have a meeting lined up with a local expert from the area, or will stop at the interpretive centre or go to any talks that might be happening.

“Many days, I don’t collect anything at all, but towards the end of my stay is when I’ll begin to gather the specimens I’ve decided on and start making my images. At this stage, you’ll find me at the campsite with all my containers spread out on the table, going through my field guides, comparing my finds, and recording their names to keep all that information organized. Then I set the scanner up and start making images.

“Sometimes an arrangement comes together really quickly: a seedpod will burst open when I place it on the glass, creating its own enchanting cloud. Other times, it’s a time-consuming challenge trying to get dozens of stalks of dried grasses to line up just the way I want. If I’m working with fungi, sometimes I’ll leave the arrangement on the glass and come back to do another scan every hour or so–as the spores begin to drop from the mushroom they can create some lovely clouds.

“If it’s still light out once the images are complete, I’ll usually do the rounds taking the specimens back to where they were collected before heading back to camp to cook dinner, read a book, and crawl into the Alfresco Science Machine for a very good night’s rest.”

Have you had many memorable encounters with wildlife in the field?

“I have seen so many amazing places, just in my exploration of Western Canada. I’ve pulled over on the side of a remote highway up north to watch a mother grizzly playing with her cub at the edge of the forest. I’ve seen one lone caribou emerge out of a thick forest and walk calmly along the road for just a few moments before disappearing silently back into the bush. I’ve seen streams and rivers thick with salmon runs. I’ve woken up in a campground to see a small group of bison sleeping two sites over.

“Most people are all about the charismatic megafauna, but it might give you a better sense of my fondness for charismatic microflora, as I like to call it, to tell you about the time my partner was driving when we were leaving the Giant Cedars Boardwalk in BC just as darkness fell. He flipped on the headlights and started to roll out of the parking lot when I shouted ‘STOP!’

“He slammed on the brakes, thinking I’d seen a bear or something similarly spectacular, but what I saw was (in my opinion) even cooler: a tight cluster of huge golden-orange Phaeolepiota aurea mushrooms glowing in the headlights–definitely my kind of memorable wildlife encounter!

“Another really cool experience was on a guided walk of the intertidal zone in Skidegate on Haida Gwaii. The interpreter found a Moon snail on the rocks and asked if anyone wanted to hold it. No one else was game, so she gently slid the snail, with its dinner plate-sized foot, into my outstretched hands. The Moon snail does this thing where it can take a whole bunch of water, kind of like a sponge, to expand its body, and then squeezes it out so it can fit back into its relatively small shell which is the size of a tennis ball.

“Moments after I had the snail in my hands, that’s just what happened. I still remember the feeling as a flood of warm seawater poured through my fingers, as the snail wrung itself out and slowly shrank and shrank. At the last moment, the shell rolled over in my hands, and I watched as the last of the foot disappeared into the shell, and it firmly closed a little door (called the operculum) behind itself. We took the hint and gently returned it to the rocks to go about its business.”

What signs did you witness of human activity and its effect on these ecosystems, if any? Were there any stark reminders of our impact on these wild places?

“I’ve seen so many wonderfully wild and protected places, but since part of my ethics of making work is to actually stay in relatively accessible places rather than traveling to (and thereby disturbing) deep untouched wilderness, I wind up doing most of my work right along that very blurry line where humans and wilderness are rubbing up against each other.

“Some of the things that have deeply disturbed me that I will never forget: driving along highways in forested areas of BC and seeing huge swathes of clearcutting, the ground blood-red with the smashed-up remains of cedar trees, barely concealed by thin ‘vanity’ lines of trees left standing along the roadside. Walking around during the heat dome in June of 2021 and watching as every leaf and fruit seemed to dry up, becoming a desiccated ghost of itself in front of my eyes.

“Visiting a grove of ancient firs with their trunks stuck full of lapel pins like some kind of weird bulletin board, representing visitors from all over the world, the forest floor littered with little memorial shrines of plastic toys and painted rocks. Walking at the foot of a glacier and seeing stacks of stones made by human visitors every few feet, in all directions, as far as I could see.

“Paddling through a marsh and having every second plant come up as an ‘introduced’ species on my plant ID app. Seeing a man buzzing around and around an eagle’s nest with his drone. Driving for hours and hours on end through thick clouds of wildfire smoke. The human footprint feels both overwhelming and endlessly pervasive at times.”

What kinds of specimens do you look for? Do you have any personal favorites from your time on the road?

“On the first trip I took when I had just built the lab, I was collecting all sorts of things and then bringing them home to sort through and work within the studio once I got home. So while my first arrangements were mainly based on aesthetics, I quickly realized that I wanted to tell a fuller story with my work. Now, all the specimens in an image come from the same place.

“I research ecosystems so I can learn what to look for and how different organisms are connected, and often I’m lucky enough to discover just the right things to put together in a photograph when I’m on site. Other times, I’m responding directly to things that present themselves when I’m exploring an area: the golden amanitas popping up from the richly varied leaf litter, an assortment of wildflowers blooming together in a ditch, the moss and lichen growing together among tiny tree seedlings on a decaying nurse log.

“I think I’m most partial to fungi and moss, mostly because of the way they quietly hold the entire world together and live such mysterious lives–so different from the human experience. I think because mushrooms (the fruiting bodies of fungi) are so ephemeral, it always seems like a special thing to find one, since they come and go as they please subject to mysterious sets of conditions known only to them.

“And mosses, which look like a homogenous green carpet from the usual human point of view some five or six feet off the ground, are some of the most incredibly elaborate, delicate, and resilient little plants, that create their own microclimate and act as the cradle and nursery of future forests.

“This field season, despite the drought that has really been bad for fungi, I was very excited to find two Hydnellum species mushroom specimens, which were just the most unearthly looking things I’ve ever seen, with velvety feet (one was orange, the other a peculiar shade of lilac), an astonishing array of tiny white stalactite-like teeth under the cap, and a golden liquid beading up on one cap.

“Another favourite was my first in a series of images of a plant called Ghost pipe (Monotropa uniflora). It’s an unusual plant that is a ghostly white, has no chlorophyll, does not photosynthesize, and primarily gets its nutrients via an alliance with fungi. I found a cluster growing in the woods, on a moss-covered piece of lumber, part of the last rotting remains of the frame of a cabin that once stood there. The ghost plant growing on a ghost cabin was such an evocative image to me–and it’s one that does give me a bit of hope that these places can recover one way or another if we leave them be.”

Are there any ethical guidelines you follow when working on this project?

“I only ever collect things that I observe growing in abundance–and certainly never any species at risk. Whenever possible, I collect things like leaves, twigs, or lichens that have already fallen off rather than removing them from a tree or plant myself. I don’t work with live animals, so any insects you see were already deceased when I collected them, and things like snail or crab shells are empty stand-ins for the live ones observed on site.

“I research the places I visit ahead of time so that I can avoid inadvertently collecting any sensitive materials, and I keep my field guides and the iNaturalist Seek app handy to confirm species IDs before I collect things, always erring on the side of caution if I’m unsure. I spend a lot more time looking around a place than I do collecting things. By the time I’m ready to make an image, I have a pretty clear sense of what elements I want to include and often find myself composing an image in my hand. I’m very mindful about my choices, gathering only what I really need to make a photograph.”

Can you walk me through your technical process a bit? Do you use a camera at any stage of the process, or are these all scans?

“I do call my work photographs, but as you point out, I’m not using a conventional camera. These photos are all created using a scanner. The model I use is a higher-end one meant for scanning photo negatives, so it has very high resolution and good colour fidelity.

“Once I’ve gathered the specimens for an image, I start to arrange the items on the glass of the scanner, which is about 9×12”. I’ll run quick preview scans to see how the composition is coming together, and make adjustments and rearrange things until I’m happy with what I see. The final high-resolution scan can take up to 20 minutes.

“I print my work at a large scale (many prints are up to six feet tall), on a super-smooth, ultra-matte paper, and I prefer to hang them with magnetic wooden bars that I build rather than a conventional frame with glass. I don’t want any barrier between the viewer and the picture. Because the paper I use has no texture, it doesn’t really read as a surface and seems to disappear, so the images feel like you could reach right into them and touch the things floating there in that inky black space.”

Is there a question you wish I’d asked that I didn’t? If so, what is it, and what’s its answer?

“I quizzed my partner for this because he always listens to my artist talks and has good questions. He asked, ‘What motivates you to arrange the items in the way you do?’

“While the original motivation to collect the items in each image is to tell a story about a place, to create a sort of portrait of an ecosystem, I also want the viewer to have a way in to identify with the living things in the photo, to see something of each organism’s ‘personality.’ Having seen all that I’ve seen, and from all the reading and research I do, I must admit that I don’t usually have a very optimistic outlook for the future of human stewardship of nature, so there’s also often a darker undertone to the images for me.

“I feel like I’m building a sort of speculative future landscape, where these might be the last little fragments of a world that is lost. Sometimes, the plants and fungi feel a bit like they are huddling together, trying to hang on as things fall apart.

“Some of the work feels more optimistic, though. In these photographs, I am trying to take some really fascinating slice of a place and hold it up to show people, at a huge scale. One of the most rewarding parts of this project is when people tell me that they now slow down a bit on their hikes, that they noticed a little mushroom, or moss, or plant and thought of me–that they pay closer attention when they are outdoors.”

All images © Julya Hajnoczky

Leave a Reply