“It’s quite powerful to be at a former campsite and realize the enormity of what was done,” says photographer Stan Honda about the injustices Japanese Americans suffered during the internment of 1942. A third-generation Japanese American himself, Stan grew up listening to stories about the experiences in the camp his parents endured. Deciding to raise awareness about this poignant era of American history, he began the documentary project Moving Walls in 1994.

“History is written by the victors” is a quote often attributed to Winston Churchill, but its origins are actually unknown. A woefully true statement, it is a reminder that there are always two sides to any historical event. One side is often lost in the dusty annals of time if it ever even had the chance for its voice to be heard. This thought probably stirred up the desire of photojournalist Stan Honda to look more closely at the internment camps of 1942, which housed some of his family members. In a project that started in 1994, Stan and his writing partner Sharon Yamato collaborated to tell the many painful stories behind these relocation centers.

Stan Honda penned a note about the terminology used in his responses: “terms such as Relocation Center were euphemisms eventually adopted by the US government as official designations. Before and during WWII the government used “concentration camps” to describe the plan to incarcerate large numbers of the Japanese American population. The term accurately describes what eventually became known as relocation centers or internment camps.

“The euphemistic terms masked the true nature of what was being done. Japanese Americans were “evacuated” — as if from a natural disaster or for their own protection — from their homes and sent to “assembly centers” and “relocation centers,” names that gloss over the fact that these were concentration, prison, or detention camps. These camps of course have no comparison to the same terms used to describe the Nazi death camps.

“”Internment,” which is a term used frequently, is the legally permissible detention of enemy aliens and does not refer to the mass forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, most of whom were US citizens.

“I use the term “concentration camp” to refer to the ten camps that incarcerated Japanese Americans during the war. This had become an acceptable term used by the community and scholars. “Incarceration” is a more accurate term to describe the detention of Japanese Americans since this was done without due process against the citizens and non-citizens alike.”

The Essential Photo Gear Used By Stan Honda

Among many photographers there is too much emphasis on the gear and not enough on the content of the photographs. Or too much on the how rather than the why. Equipment doesn’t make better pictures; it is the photographer’s skill.

The Phoblographer: Hi Stan. Please tell us about yourself and how you got into photography.

Stan Honda: I’m a professional photographer based in New York City. My background is in photojournalism. I’ve worked as a photographer for newspapers in San Diego, California, and New York. From 1996 to 2014, I worked for Agence France-Presse, the French news agency, in their New York bureau. I grew up in San Diego and attended the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Learning to shoot on film was my first introduction to photography. As a teenager, I was interested in photography, and my parents got me a Mamiya 35mm SLR camera. I took a high school class in photography, where we learned how to develop film and print pictures from the negatives. I made a crude darkroom in our garage but could only develop film or make prints at night. I worked with a friend for the high school newspaper, taking pictures of school activities. While studying psychology at UCSD, I joined the campus newspaper staff and became interested in pursuing a career in newspaper photography. After college, I got jobs at San Diego-area newspapers, eventually working for the metropolitan dailies, the San Diego Union-Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times (San Diego edition).

In 1989 I was hired by Newsday in New York and moved to New York City with my wife. We have lived here since then. I covered major stories for AFP, including politics, sports, business, and human interest. I was in New York on Sept. 11, 2001, and photographed the attack on the World Trade Center. Several of my photos were widely used, and two have become well-known. I was sent twice to Iraq to cover the war, photographed the soccer World Cup in South Africa, hurricanes in the US, the Haiti earthquake, and five years of the US space shuttle missions from Florida. Politics was a big part of the AFP coverage, and I photographed several presidential campaigns, conventions, and inaugurations. At the end of 2014, I decided to leave AFP to work on two long-term projects. One is on night sky landscapes and preserving our view of the stars, and the second is on the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans in US concentration camps.

The Phoblographer: Moving Walls – a photo project close to your heart. Please tell us what made you start this and how long it’s taken to compile it?

Stan Honda: It is not a photo project; it is a documentary project consisting of a book and a short video about the Heart Mountain camp.

My interest comes from being a third-generation Japanese American; my parents and their families were incarcerated in one of these camps during WWII. Over the years, I’ve done stories on the incarceration and the survivors. I’m also involved in groups that are helping to keep the story alive and warn that it could happen again. So I’m interested in the Japanese American story on a personal level as well as a journalistic level.

The Moving Walls project idea started in September 1994 when I met my writing partner in northern Wyoming, near the site of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, what the concentration camps were euphemistically called. The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles sponsored a project to preserve two original barracks from the Heart Mountain camp and display one of them at the museum. A group of volunteers from California had traveled to Powell, Wyoming, to dismantle two barracks that were being used by farmers as outbuildings.

In the late 1940s, after the war ended and the camps closed, homesteading farmers in the area were allowed to purchase barracks for $1 each to use on their land. The flimsy wood structures that had held incarcerated Japanese Americans took on new life as temporary homes and storage buildings for the homesteaders. To see some of the structures still standing after over 50 years was amazing.

Many of the volunteers on the project were second and third-generation Japanese Americans. Some were survivors of the camps (Heart Mountain or other camps). When I heard of the project, I decided that it was something that needed to be documented. Having visited the sites of 9 of the 10 camps, there was usually nothing left of the original buildings. These barracks are a part of American history but also part of Japanese American history. It would mean much to the community to see up close one of these barracks. I think my writing partner, Sharon Yamato, thought the same.

For me, it was incredible to see the volunteers, who traveled to what is a pretty painful site of the community’s past, work on part of their history and hear their stories. The individual boards of the buildings were put on two flatbed trucks and driven to Los Angeles. About a month later, I flew to San Diego to pick up my father, and we drove to Los Angeles to see the one barrack being reconstructed. I photographed the work and heard my father talk about the barrack he lived in (at a different camp in Arizona). Again, an amazing sight to see the mostly Japanese American volunteers reconstructing this painful part of our community’s past.

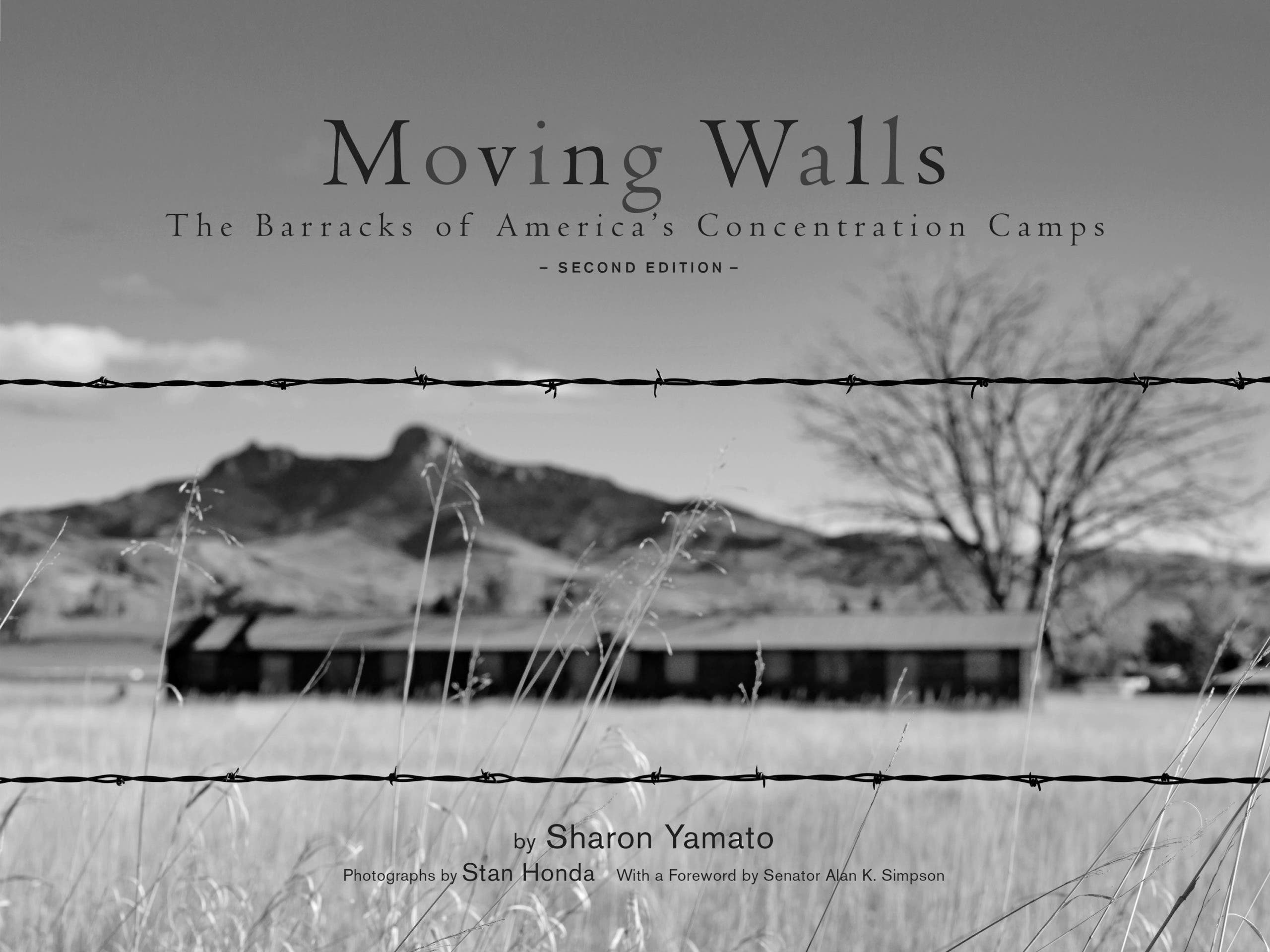

Sharon (based in Los Angeles) and I collaborated on some articles she wrote for California newspapers on the preservation of the barracks, and that turned into a small book that was published in 1995 called, Moving Walls: Preserving the Barracks of America’s Concentration Camps. It was nice to be able to show this barrack and the process of preserving it. While mentioning the shameful episode of the Japanese American experience during the war, Sharon also wrote of how she better understood her parents’ experience through these project volunteers. Her parents never said much about their wartime experience, so Sharon didn’t know any personal details.

Over the years we did small projects together, usually in California. In 2014 Sharon called to say she wanted to apply for a grant that the National Park Service ran called the Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program. Her idea was to expand the Moving Walls book and asked if I was interested in working on it. I immediately said yes; it was another opportunity to help tell the story.

In May 2015, we headed to Wyoming to research the book. It turns out there were many storages, outbuildings, and homes in the Powell/Cody area that were former barracks. Local residents would point them out to us, and Sharon interviewed several of the original homesteaders, many of who lived in a house that was originally a barrack. The history is still there in the region, in these aging structures and within the walls of ranch-style homes. I spent several weeks photographing the people and the barracks.

We took a second trip to Wyoming in July of that year to attend a pilgrimage of the Heart Mountain camp survivors and families. We were able to interview many survivors and hear about their barrack experience. A videographer accompanied us to record interviews for a short video that Sharon would make from our research. After many months of editing the images, working with a designer on the book layout, and collecting the research for Sharon’s words, the book, Moving Walls: The Barracks of America’s Concentration Camps was published in the fall of 2017. The book incorporates much of the first edition text and photos. It was great to see the final product of our work, telling the story of one part of this history. In a sense, we’ve been working on the story for 23 years, though in two short bursts.

The Phoblographer: You have family that were incarcerated in some of these camps many decades ago. What are some of the stories they’ve told from the time spent there?

Stan Honda: My parents and their families did not know each other during the war but were incarcerated in the same camp in Poston, Arizona. My mother’s family was from Orange County, California, and my father’s family was from San Diego. My sisters and I were fortunate in that our parents and many of our aunts and uncles talked about their experiences in the camps. That was unusual among people our age. Many parents refused to talk about their experiences, so the children didn’t know any personal details.

Most of what I remember my parents talking about were some of the good times they had in the camp with other family or friends. The living conditions were horrendous, and we did hear about dust and sand that would come through cracks in the poorly built barracks, the extremes in weather, and the monotonous and often bad meals. After about 6 months to a year, a camp social structure had been established at the 10 camps, mostly through hard work by the incarcerees. My father was a youth director helping with sports and other activities. My mother apparently worked for the camp newspaper as a writer; she later would write poetry as we were growing up in San Diego. She was young, having just graduated from high school before going into the camp.

My father was 24 and later on said the incarceration ruined his life. As an older nisei or second-generation person, he was allowed to travel outside the camp. He was a chaperone for the Buddhist priest, who often had to travel to several camps to minister to the congregation. My father also was allowed to travel to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to visit his father and other issei, or first-generation Japanese Americans, all men, who were arrested by the FBI on Dec. 7 or 8, 1941, and were held in the Justice Department detention camps, away from their families. He would carry letters back and forth between the fathers and their families in Poston and other camps.

The Phoblographer: Families were basically forced to pack up their lives and move into crude barracks. What was the emotional toll like on your family members, and how long did it take them to emotionally recover from this?

Stan Honda: I’m sure the toll was heavy, but I think they also kept these emotions to themselves. While often described as a “Japanese” or “Asian” trait, holding in emotions is very American, at least very middle American. There are lots of war veterans who keep things inside, and it’s difficult to understand what they went through. My parents and aunts and uncles never said they were bitter, but they probably were. My mother was younger, so it’s possible she was slightly more resilient to the wartime experience. They both saw the Midwest or east coast and have fond memories of those times.

After about a year or so after the camps were established, a person could leave as long as they went east; no one could go back to the west coast. My mother and a close sister went to Chicago to enroll in seamstress school, where they both learned sewing. I think they spent at least many months or a year before they could return to California. My father went to New York and lived and traveled in the city, finding a job at a bookstore before having to return to San Diego after a family death. The post-war experience for many Japanese Americans was extremely hard. Racism against the Japanese was often greater than before the war. People had a difficult time finding housing, jobs, and businesses that would accept them. Japanese American men who fought in the army occasionally were discriminated against while in uniform.

The Phoblographer: Do the people living in those barracks today understand the gravity of the stories their walls could tell them?

Stan Honda: We found some of the current residents of the homes made from barracks are very fascinated with the history. Some of these people are children or grandchildren of the original homesteaders. Others have purchased property with a barrack storage building on it and are trying to preserve the structure. The original homesteaders were in their 90s when we interviewed them, so some memories faded over time. Most didn’t know much about the Heart Mountain camp other than that the Japanese were kept there. All the homesteaders were returning veterans. The propaganda put out by the US government described the camps as benign and at the same time, holding dangerous people. There wasn’t a sense that the homesteaders understood the incarceration as we do now. Our sense is that until recently, many locals didn’t want to talk much about the camp being near their town.

In 2011 the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center was opened as a museum and education center that told the story of the camps and anti-Asian prejudice. The foundation that created the Interpretive Center is [made up of] survivors or descendants from the camp and locals wishing to keep the history alive. The center is on the actual campsite and provides a place people can visit for local history. I think the Center has done a lot of work within the community and people in Cody and Powell see it as a place for visitors to see.

The Phoblographer: How closely knit are the formerly incarcerated and the farmers today?

Stan Honda: From what I know, I don’t think there is a close bond between the two groups. Most of the original homesteaders have probably died. There are very few camp survivors left who have memories of the time; they would have been children in 1942-45. Once a year, the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center hosts a pilgrimage for survivors and families. I don’t know if many of the homesteading families attend. A couple of the homesteading families were active in the past in making signs to mark the few remnants of the Heart Mountain camp and trying to maintain the few structures.

The Phoblographer: How emotional was it for you to go to these sites and document them?

Stan Honda: For the Moving Walls project, it was just the one site in Wyoming. It’s quite powerful to be at a former campsite and realize the enormity of what was done. Many of the former sites are farmland now, like at Heart Mountain. People at the Interpretive Center point out the boundaries of the camp, and you realize how large and how many people were imprisoned there. At the peak, over 10,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated there. It became the third-largest city in Wyoming at the time. I think there are a lot of emotions about how the government could do this to its own citizens and how it was allowed to happen by this country. At Heart Mountain and other campsites, you also realize how isolated each place was, near a railroad track for transportation of the incarcerees, but even now there are usually only one or two small towns nearby. For a close-knit community like Japanese Americans, the disruption to lives was horrendous.

The barracks are the one artifact that camp survivors had in common. If you were incarcerated, you lived in a barrack. So everyone had a barrack story. Each full barrack was 120 feet long and 20 feet wide. Most were divided up into four sections, one for each family. You can figure out that this was not much space for living. Barracks did not have running water, so the toilets and showers were in separate barracks, and the meals were served in yet another set of barracks. It was essentially an army base for civilians. While survivors must have horrible memories of the time, they seem fascinated to see and touch an actual barrack that has been preserved. For those who didn’t have the experience, like me, seeing the structure reminds me of the warehousing a government will do to incarcerate people.

The Phoblographer: Can photographers raise awareness or even prevent such harrowing incidents from happening again?

Stan Honda: I think photographers can try to raise awareness by documenting survivors of current atrocities and showing the work widely. In 1942 there wasn’t public awareness of what was happening, and the Japanese American community had few allies or inquisitive journalists who could expose the unjust incarcerations. It takes many journalists or documentarians – photographers, writers, and videographers working together to report on these incidents. Even so, as history shows, it looks hard to prevent things like this from happening again.

The Phoblographer: Photo projects like this help keep history alive, even if it’s a history we’re ashamed of. What’s been the response to Moving Walls so far?

Stan Honda: I think about 1,000 copies of the book were printed and those have sold out. Most of the DVDs have been sold, so Sharon and I are happy that people are interested in the project. In 2018 and 2019, Sharon and I showed the DVD and spoke about our project to various groups in Wyoming, California, and New York. The responses from the audiences were good; people seemed curious about the history and daily life in the camps. The Heart Mountain Interpretive Center helped fund an exhibit of 20 of the images that traveled around the west. Here is a link to a presentation: https://sway.office.com/HwFbrFGSBfrdzVb3?ref=Link

In 2020 the University of Wyoming, Laramie, hosted the photo exhibit and an online symposium that Sharon and I spoke at that was well attended.

All images by Stan Honda. Used with permission. Visit his website as well as his Instagram, Facebook, and Vimeo pages to see more of his work. Want to be featured? Click here to see how.

Leave a Reply